Swedish Open Pairs Championships

Every year, at the turn of the month between July and August, the Swedish Bridge Festival is held in Örebro, located about two hours from Stockholm. The main pairs event of the week is the Swedish Open Pairs Championships, played over a one-day semi-final followed by a two-day final for the top 52 finishers from the semi.

My partner, Alexander Sandin, and I comfortably made the cut by finishing third in the semi-final. Unfortunately, the final was played with no carry-over, which meant we had to start all over again from scratch.

We started off well, with two pure tops in the first round. But with 100 boards to go, that was of course only the beginning. After the first of five sessions, we were in fourth place. However, our opposition for the second set would be the toughest of the event, featuring plenty of medal-winning competitors.

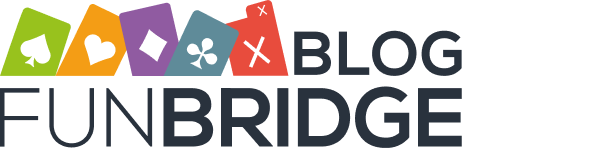

On board 31, I picked up this hand as West:

My right-hand opponent opened 3♣, vulnerable against not. Two passes followed, and Alex made a balancing take-out double. At IMPs, I might have gone for the safe option and bid 3♥, but at matchpoints there’s a strong case for passing the hand out. The main reason is the vulnerability. Even if the contract goes only one down, +200 will beat every single table playing in a part-score. And if we are actually making game, the contract might go two down for +500. Of course, there is always the risk that the contract could make, but at matchpoints that’s “just a zero”. So I decided to pass, and although declarer had seven trump tricks, those were the only ones he got. Dummy had the ♦A, but there was no way for declarer to reach it. Two down for +500 gave us a solid score, although we did lose to a few tables that got doubled in 4♣.

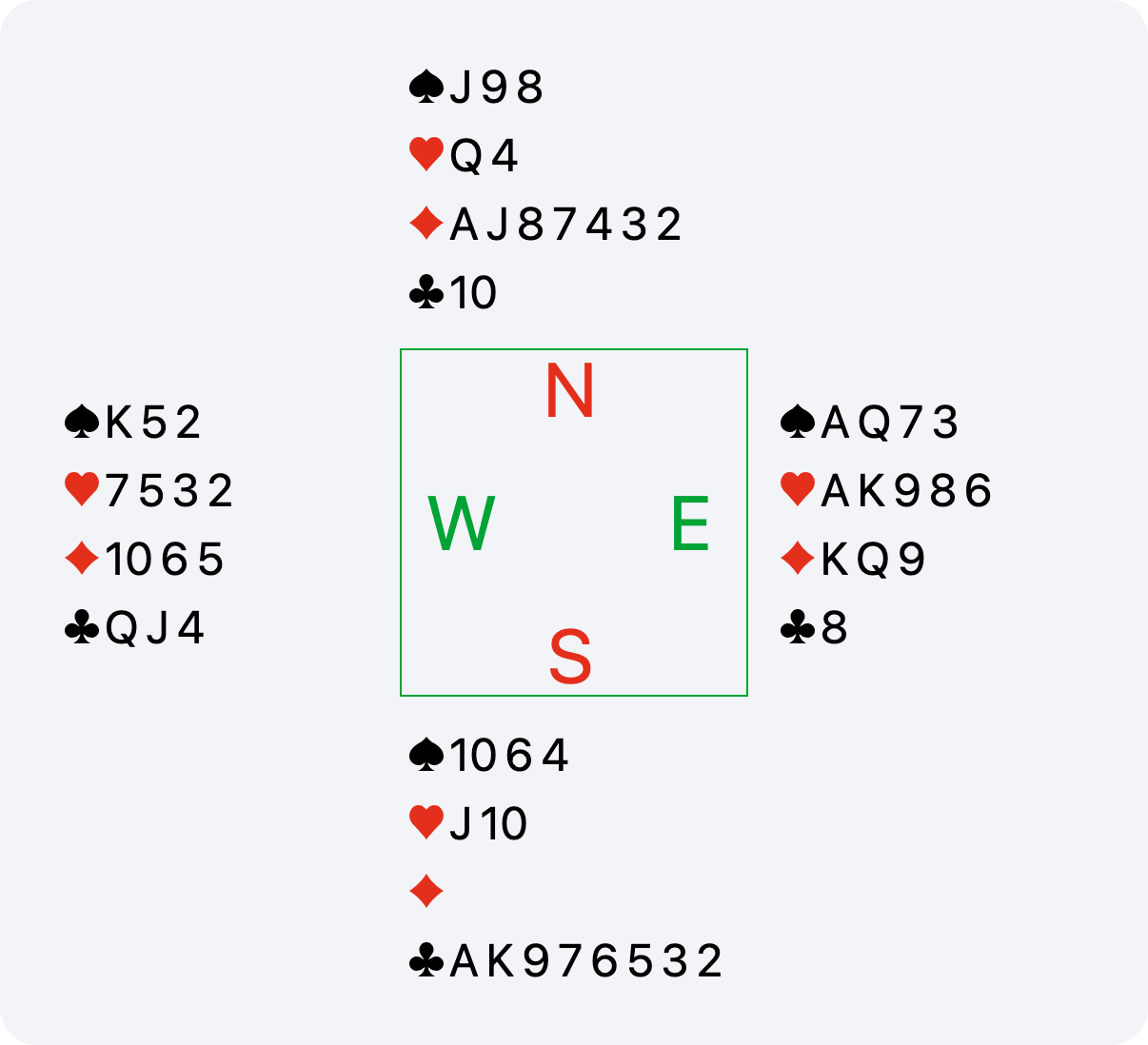

The next hand was the very last one from the second session.

East passed as dealer, and I opened 1♥. South overcalled 4♠, and Alex bid 4NT. Even though we’re not a regular partnership, this situation was covered by the so-called “Swedish junior standard”: 4NT shows either a two-suited hand with the minors or a strong heart raise. As opener, I assume he has the minors until proven otherwise.

East passed, and I jumped to 6♣. I figured Alex was very likely short in spades, and if he was willing to play at the five-level, my extras should be enough to push to slam. If the auction had ended there, we’d have been looking at around 80–85% on the board. But when Alex raised me again, the stakes went way up — I now had to play in 7♣ on the lead of the ♠A.

Alex put down the dummy and said “Good luck, I’m going to take a nap” (mind you, this was the last board of the set). I was on my own.

I ruffed the lead — had I been overruffed, there would have been no reason to waste any more energy. But when I won the trick, I paused to think for a few minutes. I played ♦K, ♣AK, and ruffed a diamond. That gave me 11 tricks. With the spade pre-emptor also holding three trumps, a 3-3 diamond split seemed very unlikely. I led the queen of spades from hand, covered by the king and ruffed in dummy; the ♠J would be my twelfth trick. Then I drew the last trump.

By the end, I knew the full shape of the hand. The only question left was: who had the ♥Q? On percentages, the finesse was a huge favourite — East had six of the seven missing hearts. But East had also passed in first seat, favourable, even with a 6-4 red suit shape. Could that mean his hearts were very weak? In the end, I took the finesse and made the grand. Then I went to find Alex and told him he was never allowed to put me through that again.

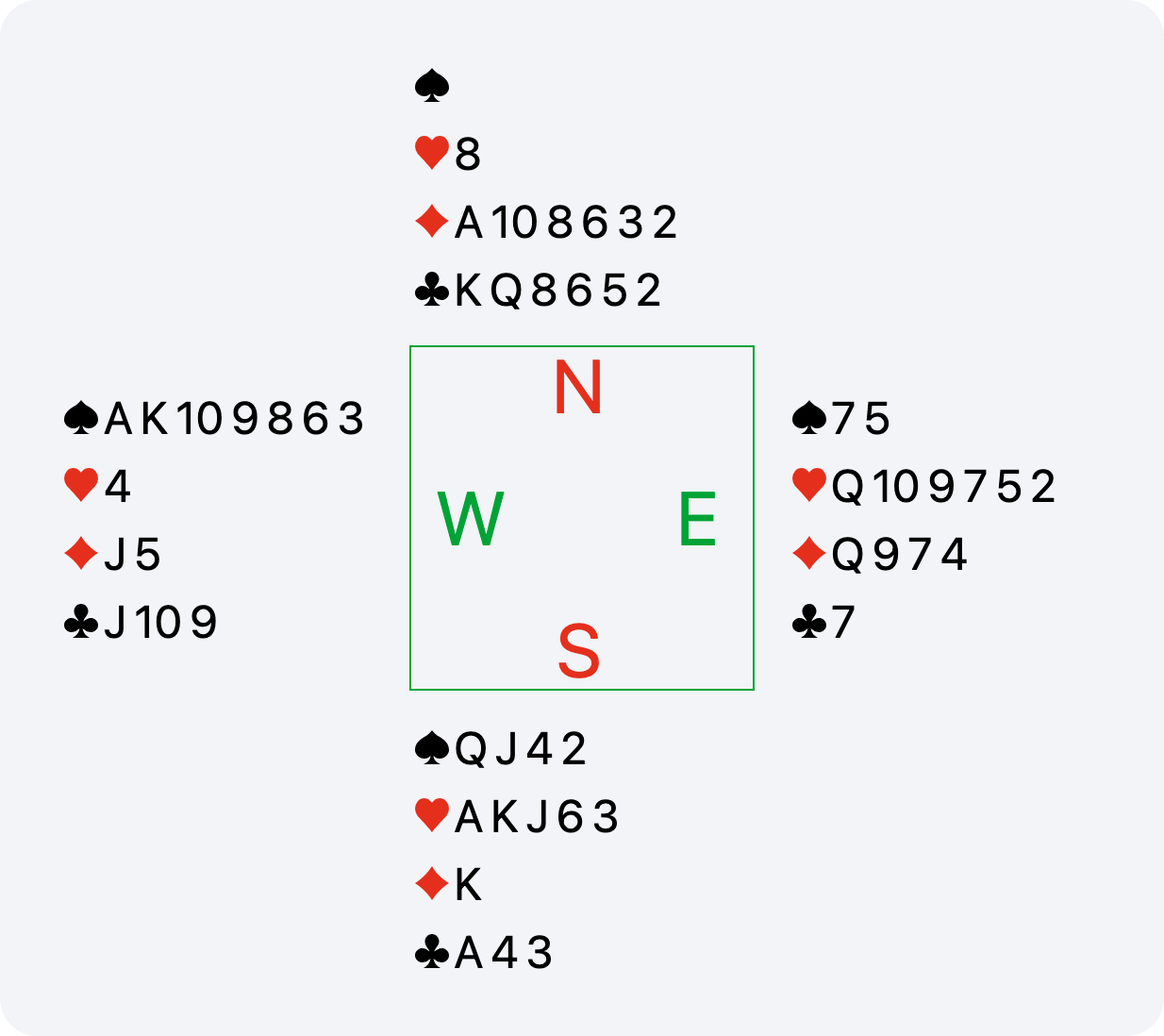

The last hand I want to share was played against the eventual silver medallists, Peter Fredin and Jan Clementsson. Fredin was declarer as East after the straightforward auction: 1NT – 3NT.

First of all, what would you lead?

In general, this is the sort of auction that screams for a major-suit lead. West didn’t use Stayman or transfer, so is likely to have at most a 3-3 major-suit holding. On the other hand, I had a five-card diamond suit. The field was divided, with a slight majority leading a diamond rather than a major. I decided on a spade. With such weak diamond spots, I thought it too likely I’d give away a trick.

Declarer won and cashed four spade tricks, and I had to discard. At the club, you might feel safe discarding a diamond. But against one of the best declarers in the world, that gives away too much information. He can see ♦AK87 in dummy and will know I wouldn’t discard from a sensitive holding unless I had length in the suit. A comfortable diamond discard is basically telling him I have five diamonds. So instead, my first discard was a heart.

Declarer then cashed ♣KQA, and I threw the ♦2 on the third club. He played a diamond to the queen, and I followed with the ♦5, holding back the ♦4. On the last spade, I pitched another heart. Then came the crucial moment: the ♦10 from hand. I ducked smoothly with the ♦6, still not wanting to give away the layout.

To be honest, I don’t always have a concrete plan for these falsecards, but sometimes an unintuitive play can mislead declarer into playing for the wrong lay-out. Fredin thought for a long time about taking the diamond finesse, but in the end played the ace from dummy, giving me the last trick with my ♦J. That was a good result for us, as many tables managed all the tricks after a diamond lead.

Alex and I went on to win the event by almost two tops, leading throughout the second half. We played with a good flow, and especially Alex played remarkably well. The victory made me the youngest ever winner of this championship, while Alex now only needs the Premier League title to join the small group of players who have won all five major Swedish events.