The Third Way: A Hypnotic Line of Play

This article is written by Guy Dupont, who has just published Promenade dans le jardin du squeeze, a work devoted to one of the most subtle and intoxicating plays in bridge. Guided by the mischievous reflections of Mazette, an iconoclastic philosopher-dog and unlucky expert, Guy leads us through the technical and poetic intricacies of this fascinating theme.

Distributed by Bridge Plus, this article extends his taste for inspired teaching, refined humor, and the meticulous exploration of the game’s inner workings. It is in this spirit that he offers us today this high-level analysis.

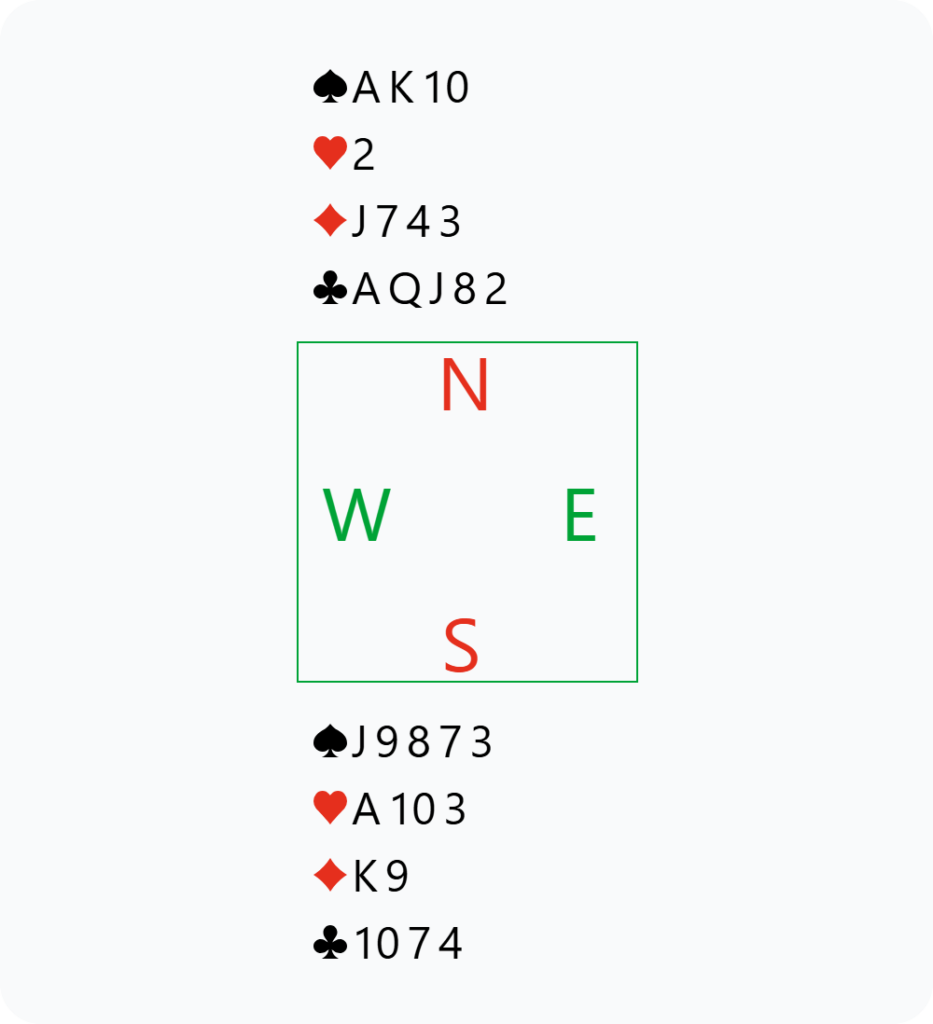

Top of the post-session commentary charts was this deal from the second round of the Top 16, France’s main teams championship. Take the South seat of Jérôme Rombaut, partnered by his son Léo (22 years old):

North dealer, North-South vulnerable

*Three cards in spades with a good opening hand.

West leads the king of hearts.

What’s your plan for the play? What did the bidding tell you?

That West held almost all the missing high cards after their 1NT bid. East could have at most the jack of hearts, or very rarely the queen of diamonds—but not the queen of spades, shown as a stopper after the NT bid. West also very likely has four hearts, having raised partner to the three-level (who might have a very weak hand). A clue could confirm this, depending on East’s signaling on the opening lead.

From there, we can easily picture West with a 4-3-3-3 distribution (with four hearts), or perhaps 4-4-3-2. So, possibly a second four-card suit. The danger would be that it is spades (possible after their 1NT overcall) or clubs (a suit in which we know that they hold the king).

After taking the lead with the ace of hearts, most players generally opted for two lines of play that were not without risk but proved successful:

- Let the 10 of clubs run at trick two, a club to the jack, then ace and king of spades, followed by cashing the clubs (discarding a diamond). This line produced eleven tricks here, thanks to friendly black suits. However, the contract would have gone down if East had a singleton club.

- Play a small diamond to the jack at trick two, hoping for the queen in West. This worked not only when the queen was onside, but also thanks to West’s very favorable 3-4-3-3 distribution. But the contract would have failed if West had held four spades: with ace-queen of diamonds doubleton (and three clubs), they would cash their two diamond tricks and a heart return would be fatal; and with ace-queen of diamonds tripleton (and two clubs), after their two diamond tricks, a return in spades or diamonds would be just as deadly.

Jérôme, for his part, did not follow these paths. He chose to duck the opening lead! A decision that opened up other horizons, depending on West’s next move.

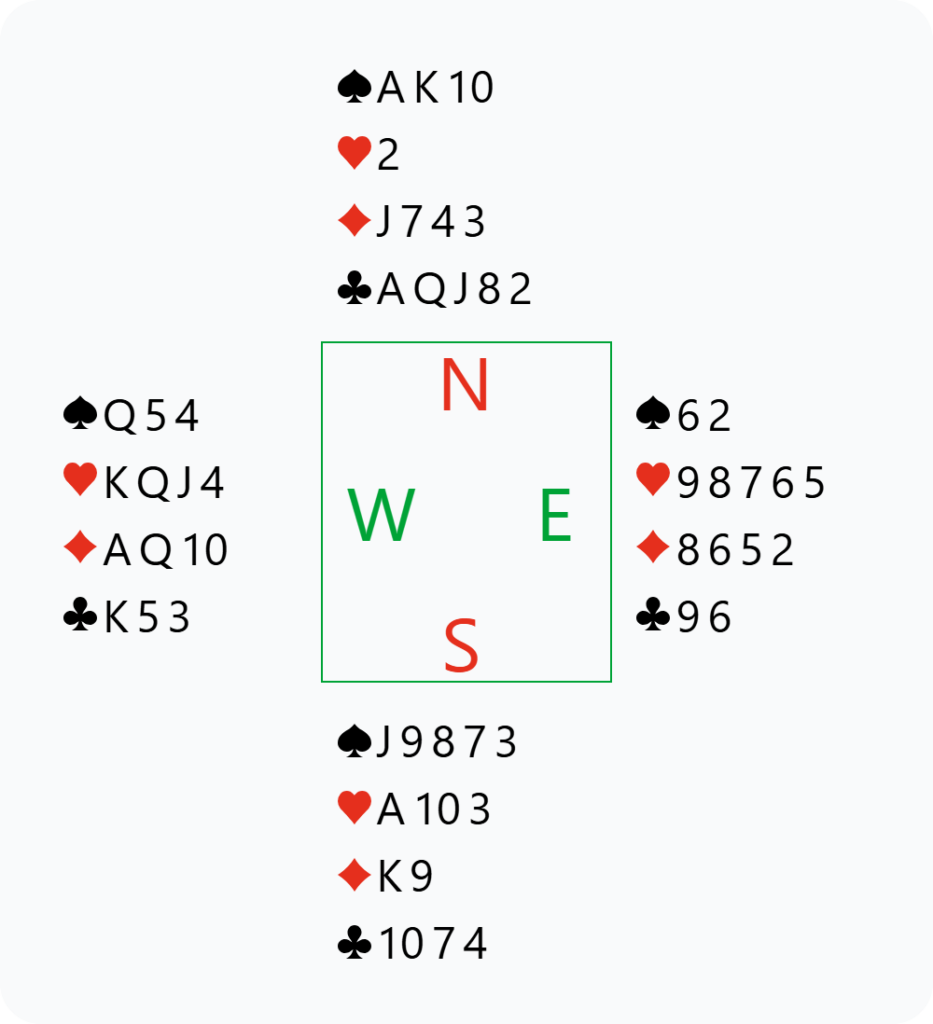

At the table, West continued with the queen of hearts. That was exactly what declarer wanted! For suddenly, it became possible to secure the contract, even if West had four spades or four clubs—or even if East held the queen of diamonds!

The heart return was carefully ruffed with the king of spades, followed by ace and 10 of spades, covered by the jack and taken by West’s queen, who persisted with a heart to the ace. South then cashed their last two trumps, and ten tricks became routine with West’s 3-4-3-3 distribution.

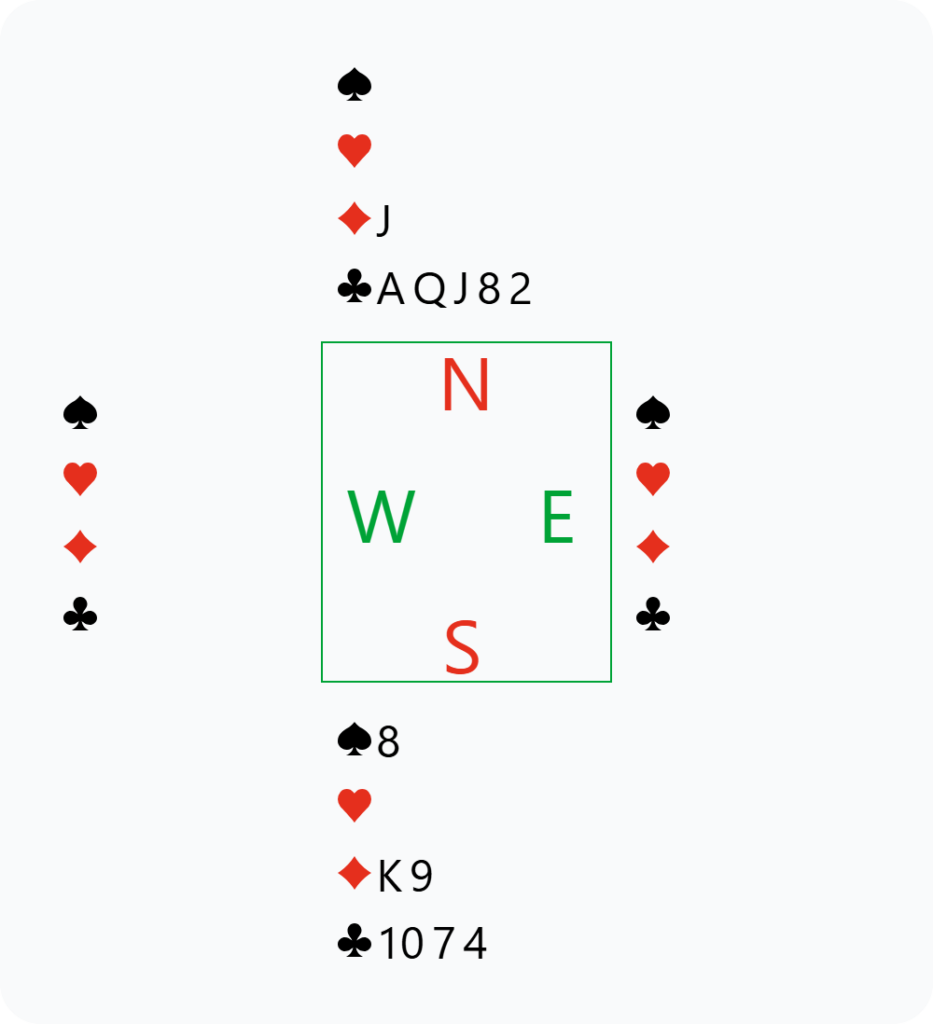

But what if West had held four clubs? We would have reached this position:

In West’s hand, we are looking at either a doubleton Ace-Queen or Ace-Ten, together with four Clubs headed by the King.

In East’s hand, the 9 and 8 of Hearts, three Diamonds headed by the 10 or the Queen, and a singleton 9.

On the 8 of spades, West discards a diamond (note that the contract would not have been in danger with four trumps in their hand, since they would have followed on the 8 of spades!), while a club is pitched from dummy. South then plays the 10 of clubs, which wins, followed by a small club to the jack. If East follows on the second round, the clubs will provide the four tricks needed to make the contract; and if East discards, declarer exits from dummy with a diamond, for an effective endplay on West, finally forcing them to play into the club tenace. Diabolical!

With these favorable black-suit splits, Jérôme lost 1 IMP on the board—others made an overtrick in the same contract in the other room, where the heart lead was taken with the ace. A modest loss, but with plenty of regrets, given the hope of a substantial 10-IMP gain.

A magnificent endplay made possible by refusing the opening lead, which put the defense on the spot, while exerting a kind of hypnotic power over them: how could West resist returning a heart, seeing dummy’s three trumps, to tempt declarer into ruffing and thus deprive them of a successful spade finesse?

However, what if West had switched to spades?

The winning line would have become trickier. Declarer would probably have feared a switch into three or four trumps and, to secure the contract in that scenario, they would have had to give up hope of winning if West had four clubs. The best plan would then have been to call for the king of spades and continue with ace and 10 of spades, covered by the jack—hoping that the clubs would behave.

Note that there would still have been a winning line with four clubs in West (who, in that case, would probably have had only three spades—let’s ignore the case of a singleton ace of diamonds!). Declarer would need to play the 10 of spades and eliminate the trumps, possibly after covering the 10 of spades with the jack and attempting an initial club finesse. Riskier.

In conclusion: great credit to declarer for choosing this third way, which could have led to a play from the third dimension. It rested on that good old bridge principle dear to Mazette the dog: the opponent has the right to make a mistake—let’s give them the chance!